Blaeu Atlas of Scotland, 1654

| Field | Content |

|---|---|

| Name: | Blaeu, Joan, 1596-1673 |

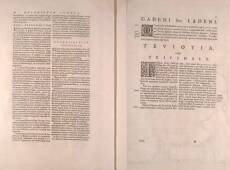

| Title: | Scotiae. Gadeni sive Ladeni; Teviotia, vulgo Teifidale |

| Pagination: | 30-31 |

| Zoom view: | Click on the image to view in greater detail |

| 34 / 162 Scroll through pages:

| |

Translation of text:

ecclesiastical matters of that kind are dealt with. In the other individual parts of the Kingdom there are individual judges for these, from whom there is a right of appeal to the four Commissaries of Edinburgh.

SHERIFFS’ COURTS

There are also lower civil courts in each County, in which a Sheriff or a person delegated by him dispenses justice to the inhabitants on ejections, intrusions, losses, debts etc. From them appeals are sometimes made to the College of Justice because of inequity or reason of affinity. The Sheriffs whom I describe are mostly all hereditary. For the Kings of the Scots, just as those of the English, in order to tie the nobles more firmly to them by rewards, formerly appointed hereditary and perpetual Sheriffs. But the inconveniences that arose from this were perceived at once by the English, and they deliberately changed them to annual appointments. Civil courts are also held in Royal feus by their Bailie, who by the munificence of the King has achieved regal liberties, and also in free burghs and towns by Magistrates.

The Sheriffs are judges of regions; they do not judge on lands, but only on small matters, which do not exceed a value of £100 Scots; on these appeal is allowed to the Supreme Senate before sentence is passed. Almost all were formerly hereditary. But Kings James VI and Charles I redeemed these jurisdictions for much money from all (with the sole exception of the Earl of Rothes); so that now each year the King chooses one lesser Baron from that Sherrifdom; his name is sent to the Director of Chancery, who gives him a diploma to be sent to the Chancellor, who supports it with the great seal of the Kingdom. Whose son obtained the same from the King [?], they judge within 48 hours concerning thefts, murders and other capital crimes, but when the crime is flagrant they can at least slander them on their own authority, but if that is obtained from the Privy Council he can always and everywhere prosecute according to the tenor of the Commission. If friends of the dead man have captured the murderer, they can hand him over to the Sheriff, who can in this case too pass judgement and either hang or drown him.

Now when sentence has been passed the condemned party of a decreet by hanging is often accustomed to appeal to the Supreme Senate of Council and Session, where the process led before the Sheriff is again examined, whether the sentence was passed well or badly.

Sheriffs also in their territories and magistrates in some Burghs enquire into murder (the murderer being apprehended within the space of 24 hours) and inflict the ultimate penalty on an accused condemned by the jurors; but if that time has elapsed, the case is referred to the King’s Justiciar or his Delegates. Some nobles also enjoy the same privilege against robbers apprehended in their jurisdictions. Some too have Royal rights of such a kind that they exercise jurisdiction in criminal cases within their boundaries, and in some cases recall persons living within their areas from the King’s Justiciar, however a caution having been pledged that they will give justice by the law.

ECCLESIASTICAL GOVERNANCE

The ecclesiastical governance of Scotland is this.

First, each Sherrifdom is divided into places of Sessions, and these into parishes, according to size and as numbers dictate. From parishes presbyteries are made up.

The Session of a Church is when the minister with the Elders and Deacons meets once a week, to look into the morals of his flock, to correct sins, to enjoin penitence on the guilty, only with regard to fornication or adultery, quarrels, violation of the Sabbath, etc. If anyone thinks himself injured by that judgement, he can appeal to the presbytery of his Church.

Each presbytery has its own churches, 10, 15, more or less, according to the size of the population and the kind of district; in each province there are 4, 5 or more presbyteries.

The presbytery is the gathering of all the ministers, when under such a presbytery each minister has with him one of the Elders of his Church as it were joined to him. They meet each Thursday in the appointed city, and after a sermon hear appeals, if there are any, and decide them. If the accused wishes to appeal again from there, it is done to the Synod of his province. That Synod meets twice a year, once in April and once in September. All the ministers and the same number of Elders meet for this Synod, and it lasts for one week. Appeal is allowed from this provincial Synod to the general one of the whole Kingdom. This Synod is proclaimed for the beginning of July and ends before the harvest, that is the feast of St Peter.

The general Synod decides eveything without any appeal, and makes acts for the governance of the whole Church of Scotland, but these acts have to be ratified by Parliament. To that general Synod are sent as delegates from each presbytery one minister with one Elder.

In this Synod erring ministers are ejected; they are transferred according to the petitions of the cities.

GADENI or LADENI. (Section Note)

Neighbouring the Otadini or Northumbria were the GADENI, who are called LADENI in some copies of Ptolemy, with a change of one letter. They lived in that region which lies between the mouth of the River Tweed and the Forth at Edinburgh, and is today divided into many sub-regions, of which the chief are Teviotdale, Tweeddale, the Merse, and Lothian (in Latin Lodeneium); under this last name all were included in writers of the Middle Ages.

TEVIOTIA,

in the vernacular

TEVIOTDALE. (Section Note)

Teviotdale, that is Valley of the River Tefius or Teviot, among the steep borders of hills and rocks, close to England, is inhabited by a warlike people, who on account of the very frequent wars in previous centuries between the Scots and the English, are highly prepared for military service and sudden attacks.

Among them the first town is Jedburgh, a well-populated burgh, near the confluence of the Rivers Teviot and Jed, whence comes its name. Also Melrose, a fairly old monastery, in which while the Church stood high in our land the monks were of that old character, who had leisure for prayers and sought their living by the work of their hands.

More to the east, where the waters of Tweed and Teviot come together, is Rosburgh, also called Roxburgh and formerly Marchidun, because it was at the boundary; here once was a castle strong by its position and by fortified towers. It had been occupied by the English, and while James II, King of Scots, was besieging it, he was killed prematurely by a piece of a large gun which chanced to explode, in the flower of youth, much regretted by his people. The castle was surrendered and to a large extent levelled, and has now in a measure disappeared. The adjacent territory, called hence the Prefecture of Roxburgh, has its own hereditary Prefect or Viscount from the Douglas family, called in the vernacular the Sheriff of Teviotdale. Now however Roxburgh, thanks to King James VI, also has its own Baron, Robert Ker, from the family of Kerrs which is in this area especially famous and numerous; among them those of Ferniehurst and others, nourished in the study of war, have become most distinguished.