About the Stevensons

The Stevenson engineering firm operated in Scotland from the late eighteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. In 1787 the newly-established Northern Lighthouse Board appointed Thomas Smith, an Edinburgh-based lamp-maker, to construct and manage four lighthouses on the Scottish coast. He was assisted by his stepson and apprentice, Robert Stevenson, who demonstrated a talent for civil engineering. On Smith’s death, the business was divided. His son, James Smith, inherited the lamp-making firm while Robert took over as engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board and used this as the foundation of the civil engineering firm that bears his name.

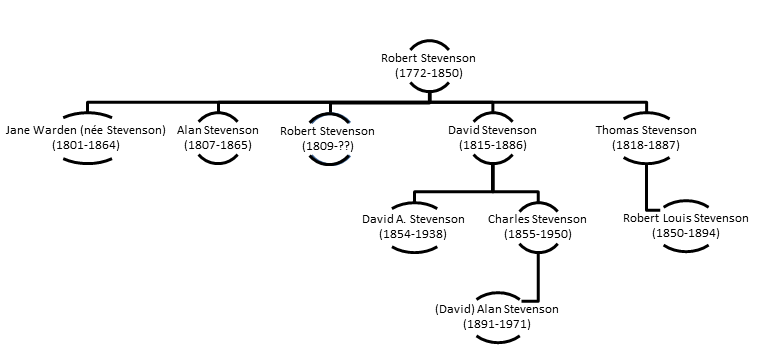

Three of Robert’s sons, Alan, David and Thomas, became engineers with the family firm when they reached adulthood. The firm subsequently passed to David’s sons, David Alan and Charles in the 1880s. Charles’ son, D. Alan, became a partner in 1919.

While the firm continued to specialise in lighthouse design and serve as engineers to the Northern Lighthouse Board until the 1930s, they also took on a variety of private practice work. Where nowadays engineers often specialise in a specific type of construction project, the Stevensons were generalists who turned their hands to a variety of different kinds of work. They took on projects ranging from harbour improvements to water supply works, sewer construction and urban planning to the development of new lenses, fog signals and electric light. They were involved in scientific societies, including the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the Royal Scottish Society of Arts and the Institution of Civil Engineers and they published academic papers in fields as various as meteorology, optics, geology, oceanography, hydrology, acoustics, electricity and engineering history.

Family Members

- Robert Stevenson, 1772-1850

- Jane Warden (nee Stevenson), 1801-1864

- Alan Stevenson, 1807-1865

- David Stevenson, 1815-1886

- Thomas Stevenson, 1818-1887

- Robert Louis Stevenson, 1850-1894

- David Alan Stevenson, 1854-1938

- Charles Stevenson, 1855-1950

- (David) Alan Stevenson, 1891-1971

Robert Stevenson, 1772-1850

© National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Born in Glasgow in 1772 to Alan and Jean Stevenson, Robert Stevenson moved to Edinburgh as a young child after the death of his father in St. Kitts. Shortly after this, his mother met and married Thomas Smith. Smith was the first engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board – the body responsible for the construction of lighthouses in Scotland – from its foundation in 1786. Robert trained under his stepfather and attended lectures at the University of Edinburgh, but had no formal qualifications in engineering when he took over his step-father’s business in 1800 and became responsible for Scotland’s lighthouse service.

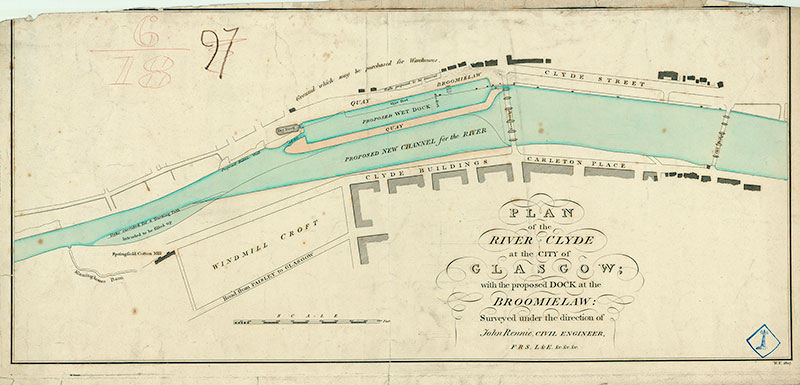

Robert’s most famous achievement was the construction of a lighthouse on the Bell Rock, a partially submerged reef in the North Sea 27 miles east of Dundee. On average, 6 ships were wrecked there every winter. A lighthouse there would make travel around Scotland much safer, but the rock’s isolated location, the fact that large parts of it were submerged by the tide and the ferocity of the waves and wind in that part of the North Sea presented significant challenges to the engineer. Robert proposed a design to the Northern Lighthouse Board who consulted John Rennie, a leading engineer of the day. The design was eventually approved and constructed under Robert’s immediate direction as Resident Engineer, with Rennie as consultant. The project was begun in 1806 and completed only five years later in 1811 and still stands today.

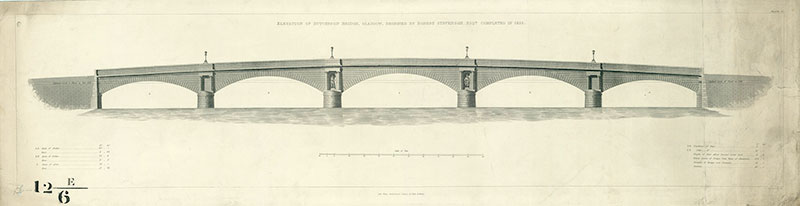

Robert’s work in later life varied considerably, encompassing fields of expertise that lay far outside the lighthouse business. He was heavily involved in the remodelling of Edinburgh’s city centre, designing Waterloo Bridge to connect Princes Street to Leith Walk at the base of Calton Hill. He designed bridges, including Hutcheson Bridge (replaced by Albert Bridge in the 1860s) in central Glasgow in 1834.

From the 1810s, he was involved in surveying land in preparation for railway construction. At that time, railways were in their infancy. The steam engine was not in general use until the late 1820s. Instead, waggons were dragged along railway lines by horses primarily to transport goods – particularly coal. Robert saw the potential of the new technology and suggested several innovations, including the regulation of railway width and the possibility that the railway might eventually carry passengers. Few of his railway lines were ever carried out, possibly due to the expense of construction, but he was still recognised as an authority in this field.

Robert married Jane Smith in 1787 and the couple had 13 children. Five lived to adulthood. Three of his sons and his daughter were all involved in the family engineering business as adults. The fifth child, Bob, worked for the family firm for a short time before becoming an army doctor and serving with the 3rd East Kent Regiment of Foot in India until his death.

Robert died in July 1850. He was commemorated fondly by his sons and by the Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouse Board who arranged for a bust to be placed in the Bell Rock Lighthouse in his memory.

Back to listJane Warden (nee Stevenson), 1801-1864

Although she was not an engineer, Robert’s daughter Jane Stevenson was no stranger to the business that occupied the men in her family. She was the original addressee of a series of letters narrating an engineering tour Robert took in 1817. He published these letters as Journal of a Trip to Holland. In 1820, she accompanied Robert and her brothers on their travels around Scotland to inspect the Northern lighthouses. In later years, she provided secretarial support to her father and was instrumental in organising the company’s reports and paperwork.

Jane’s contribution to the archive is more subtle than that of her brothers, her organisational work in managing the company’s papers is acknowledged in a brief note from Robert in the index to his report books:

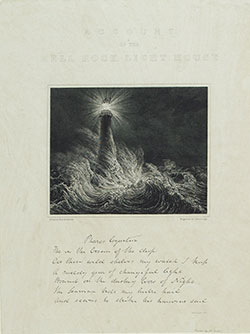

Jane’s own work can be seen in Robert Stevenson’s 1824 book, An Account of the Bell Rock Light-House. She was heavily involved in the production of the book, acting as her father’s secretary and taking dictation throughout the writing process. The title page features a drawing by Jane of the Bell Rock alongside some verses written by Sir Walter Scott on his visit to the lighthouse in 1814:

O’er these wild shelves my watch I keep:

A ruddy gem of changeful light,

Bound on the dusky brow of night.

The seaman bids my lustre hail,

And scorns to strike his timorous sail.

'Pharos Loquitur' Sir Walter Scott (1814)

Alan Stevenson, 1807-1865

Robert’s eldest son Alan joined the family business as an apprentice in 1823, aged 15. He combined his training under his father with education at the University of Edinburgh where he studied mathematics, chemistry, natural philosophy and mineralogy among other subjects. His education took the form of classes during the winter and site work during the summer as the Scottish weather prohibited building progress during the winter months. Alan was awarded an M.A.Phil. in 1826 and received a Fellowes Prize. During the summers he gained practical skills, working with Thomas Telford and James Walker on Hull docks, learning railway surveying from William Blackadder of Glamis and travelling in Sweden with Robert Bald. He also worked on numerous projects for his father including surveying a possible canal route in Forfarshire, supervising bridge building at Annan and lighthouse construction on the Rhinns of Islay. He became a partner in the firm in 1832.

In 1834 Alan travelled to France to learn from the Fresnel brothers, Augustin and Léonor, renowned physicists who specialised in optics. While there, he learned of Fresnel’s dioptric apparatus which used lenses instead of mirrors to focus light and could therefore produce a more intense beam. He subsequently introduced this form of lighting to Scottish lighthouses, beginning with the light at Inchkeith in 1835.

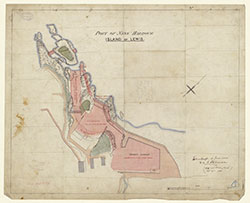

As Robert got older and found it more difficult to manage the strenuous travels and site work required for the lighthouse service, this was increasingly delegated to Alan. It was Alan who designed lighthouses at Little Ross in 1843, Covesea Skerries in 1846, Noss Head in 1849, Hoy in 1851 and Stornoway in 1853, among other places.

Alan’s best known achievement was building the lighthouse at Skerryvore, an isolated outcrop 12 miles off the coast of Tiree in the Inner Hebrides that was frequently battered by the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. Originally singled out as a possible lighthouse site by Robert in 1804, permission was granted for the work in 1814 but it was not commenced until 1838 due to the prohibitive costs of building in such an isolated location. Alan took charge of the building, spending much of the following years living with the workmen in a tiny barracks on the rock itself and overseeing construction, Skerryvore was eventually completed in 1844. Louis wrote the following poem on visiting Skerryvore:

Of those, my kinsmen and my countrymen,

Who early and late in the windy ocean toiled

To plant a star for seamen, where was then

The surfy haunt of seals and cormorants:

I, on the lintel of this cot, inscribe

The name of a strong tower.

‘Skerryvore’ Underwoods. Robert Louis Stevenson (1887)

Unfortunately, Alan’s career as an engineer was cut short. After a lifelong battle with poor health, worsened by constant travel and outdoor work, creeping paralysis eventually prohibited him from engineering work. He resigned from the family business in 1853 and his work was taken up by his younger brothers David and Thomas. He lived in quiet retirement until his death in 1865.

Back to listDavid Stevenson, 1815-1886

Like his brothers, David Stevenson was raised with the expectation that he would become an engineer. He happily followed this career path, beginning an apprenticeship with his father in 1831 at the age of 15. His apprenticeship would see him put to work on a variety of ongoing projects with the firm. He also took classes at the University of Edinburgh during the winter months from 1831-1835, studying chemistry, natural philosophy and agriculture. On graduation, he took a job working at Granton Harbour for the Duke of Buccleuch but resigned at the end of the year after a dispute with the Duke. He used this income from this post to make a tour of the United States, finding out how American engineers were addressing problems in river and railway work. He published an account of what he encountered as Sketch of Civil Engineering in North America (1838).

On his return from this tour, David was made managing partner of the family firm. He decided to pursue a varied portfolio of work and to continue to take on other projects alongside the ongoing commitment to the Northern Lighthouse Board. While this could occasionally leave the family stretched thin, it provided additional regular income and new technical challenges for the brothers to address. These projects included harbours of refuge on the east coast, railway survey work, consultation on river navigation improvements at the Tay, Forth and Clyde.

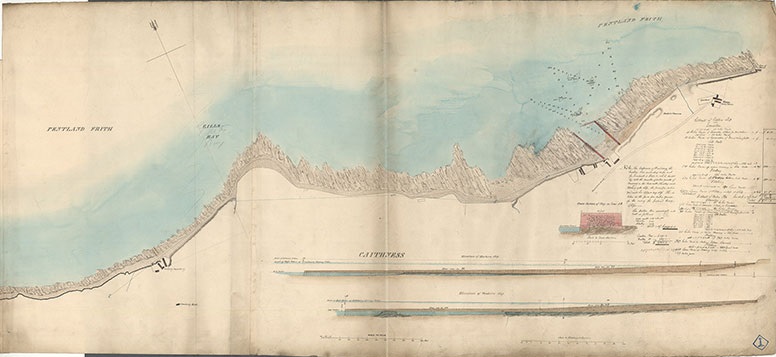

After Alan’s health deteriorated and forced him to retire, David and Thomas shared the role of engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board. They redesigned the lighthouse role, delegating much of the management to a secretary. This allowed them to focus on the technical aspects of the engineering itself. The work of lighthouse construction continued, spurred on by the outbreak of the Crimean War and a newfound urgency from the navy to ensure that routes around the Northern Isles were safely navigable for warships. David was given this task in February 1854. He travelled north to survey the area and chose Muckle Flugga, a small rocky island north of Unst in the Shetland Isles as a location. He designed the light and supervised its construction over that summer. It was lit on 11th October 1854, a remarkable feat, even though it was only intended to be a temporary light used during the war.

By sharing the lighthouse work, David and Thomas were both able to work on other projects in line with their personal expertise and interest. For David, this meant advising the government and improvement works to canals and rivers. In the 1870s alone, the firm produced seven different reports evaluating and suggesting works on the Clyde. In total there are almost 100 plans relating to the Tay in the collection, many of which date from the period of David’s management.

<

David’s approach to engineering was immensely practical. His Principles and Practice of Canal and River Engineering used real world examples to show how theories of hydrography could be used in engineering. He served as President of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts in 1867 and used the opportunity of his Presidential Address to argue against general education because ‘we shall err greatly if it is made so general as to fail in producing substantial practical results.’ Where Thomas favoured experimentation, David, in the words of biographer Craig Mair, ‘gave the firm solidity and dependability.’

David retired in 1883 after falling ill in 1881. He died in 1886. His work was taken over by his son David Alan. David Alan worked with Thomas until the latter retired in 1886 and was replaced as a partner by David’s younger son, Charles.

Back to listThomas Stevenson, 1818-1887

The youngest of Robert’s children, Thomas was the most innovative and experimental. Although he followed the his brothers through the University of Edinburgh into an apprenticeship at the family firm, Thomas was more interested in studying and understanding the natural world that he encountered in his work. He was constantly devising and carrying out experiments. Where the instruments and measuring techniques in existence did not provide sufficient data for his needs, he would often invent his own devices. In 1843 while working on waves, he built a marine dynamometer - a device that used compressed springs to measure how much force was exerted by waves striking the coast. In the 1870s, he invented the Stevenson screen which aimed to standardise the environment in which weather measurements were taken between different weather stations. Constant research led him to publish 98 academic papers in his lifetime on subjects as varied as optics, meteorology and wave dynamics.

Thomas was also a committed civil engineer, applying his inquisitiveness to subjects related to his work. In particular, his work on waves informed his harbour and lighthouse design. His theories were tested in the real world with mixed success. The majority of his projects were successfully constructed, but some – for example Anstruther Harbour – were not initially robust enough to survive the winter storms of the North Sea and needed to be redesigned and repaired while in progress. Only one harbour defeated Thomas completely. Referred to as ‘the chief disaster of my father’s life’ by his son Louis, the harbour at Wick was destroyed by winter storms several times before the British Fishery Society were no longer able to finance the repairs and the project had to be abandoned in 1877.

Despite this mixed success in harbour work, the Stevenson firm under David and Thomas was extraordinarily busy elsewhere. The brothers produced reports on subjects ranging from fog signals to silt levels in the Manchester ship canal and designed harbours on Mull, Skye, Lewis and North Uist, to name just a few. International acclaim followed their domestic work and the Stevensons were increasingly asked to design lighthouses for foreign waters, including in Japan from 1867 and New Zealand from 1876.

After David’s retirement in 1883, Thomas worked with his nephew David Alan and Alan Brebner for a few more years. He eventually retired in 1886 and died shortly after in 1887. Thomas was replaced as a partner by his nephew Charles and a new generation of the firm, this time called D. & C. Stevenson, began. He was remembered by his son as follows:

Puts daily home; innumerable sails

Dawn on the far horizon and draw near;

Innumerable loves, uncounted hopes

To our wild coasts, not darkling now, approach;

Not now obscure, since thou and thine art there,

And bright on the lone isle, the foundered reef,

The long, resounding foreland, Pharos stands.

These are thy works, O father, these thy crown;

‘To My Father’ Underwoods. Robert Louis Stevenson (1887)

Robert Louis Stevenson, 1850-1894

More famous as the author of novels such as Kidnapped, Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson began his life as a trainee engineer. The only son of Thomas Stevenson, Louis was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps, and studied engineering at the University of Edinburgh from 1868. During the summer months, he was despatched to the sites of various family works to learn in the field, working on Anstruther and Wick harbours in 1868 and touring the Scottish lighthouses with his father in 1869. He was awarded a silver medal for a paper on 'A New Form of Intermittent Light' by the Royal Scottish Society of Arts in 1871.

This marked the end of his career in engineering. While enamoured with the travel and adventure made possible by his father’s profession, Louis did not have the same passion for the work as the rest of his family. In 1871 he told his father that he wished to give up engineering and become a lawyer instead. Soon after that, he became a full time writer.

Louis’ writing included vivid descriptions of many of the places and experiences that must have characterised his early life as a trainee engineer. He wrote evocatively of the sea, of isolated islands, cramped ships and sailors. He also wrote biographical and autobiographical accounts of the family business, including Records of a Family of Engineers, which focused mostly on the work of his grandfather in building the Bell Rock. He wrote short essays and poems recounting his own early experience studying in Edinburgh and as a student engineer travelling around the country and recalled the family’s achievements with pride.

The labours of my sires, and fled the sea,

The towers we founded and the lamps we lit,

To play at home with paper like a child.

But rather say: In the afternoon of time

A strenuous family dusted from its hands

The sand of granite, and beholding far

Along the sounding coast its pyramids

And tall memorials catch the dying sun,

Smiled well content, and to this childish task

Around the fire addressed its evening hours.

'Say not of me, that weakly I declined' Underwoods. Robert Louis Stevenson (1887)

Although his career as an engineer was short-lived, Louis played an important role in shaping how the family story was told through his writing.

For further information on Stevenson's life and related material held in the National Library of Scotland's collections, see the Robert Louis Stevenson web resource.

Back to listDavid Alan Stevenson, 1854-1938

© Trustees of D. Alan Stevenson

The eldest son of David Stevenson, David Alan Stevenson was born in 1854 and educated, like his father, at the University of Edinburgh. He graduated with a BSc in Engineering in 1875 and began a formal three-year apprenticeship at the family firm. He became a partner in 1878. Alan Brebner, a long-term assistant in the firm, was made a partner at the same time as David and was the only non-family member to be made a partner in the Stevenson firm from its foundation.

David was a member of a number of learned societies, including the Royal Society of Edinburgh from 1884 and the Institution of Civil Engineers from 1886. He was awarded multiple prizes for his papers by the Institution of Civil Engineers. He and his brother also updated many of the works of their father and uncle, publishing new editions of their books and rewriting entries in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The Stevenson’s work for the Northern Lighthouse Board also occupied much of David’s time. After his father retired, he worked with Thomas to design lighthouses at Fidra in 1885 and at Oxcar and Ailsa Craig in 1886 before taking over as Engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board from 1887. He went on to build at least 18 lighthouses, including at Rattray Head in 1895, Sule Skerry in 1895 and Flannan Isle in 1899, which later became famous as the site of the unexplained vanishing of all three lighthouse keepers on the afternoon of 15 December 1900. This mysterious event garnered significant public attention and was commemorated in popular culture, for example in a poem by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson – which inspired a 1977 episode of Doctor Who:

And hunted everywhere,

Of the three men's fate we found no trace

Of any kind in any place,

But a door ajar, and an untouched meal,

And an overtoppled chair.

'Flannan Isle' Fires. Wilfrid Wilson Gibson (1912)

David Alan retired in 1938 and died a month later. He was replaced as Engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board by one of his assistants, the first time the post had been held by someone outside of the Stevenson family since its creation.

Back to listCharles Stevenson, 1855-1950

© Trustees of D. Alan Stevenson

Charles Stevenson, like his brother, graduated with a BSc in Engineering from the University of Edinburgh in 1877. The brothers travelled to America together soon after Charles graduated to observe international engineering practices and inventions. On returning to Scotland, Charles joined the family firm to complete his training as an engineer. He was made a partner in 1887. On the death of Alan Brebner in 1890, the brothers changed the name of the firm to D. & C. Stevenson.

Where David focused on lighthouse work, Charles was responsible for much of the other business conducted by the firm. During the 1870s and 1880s, the brothers worked alongside their father and uncle across Scotland, although the firm increasingly specialised in engineering related to water. Ongoing development and repair works to small local harbours continued to provide much of their daily work. They were involved, for example, in harbour works at the Port of Ness in Lewis (1883-1891), Balintore on the Moray Firth (1888-1893), Brodick on Arran (1898), Nairn (1891-1901) and Pittenweem in Fife (1902-1929). The Stevensons were also consulted on the extension of sewers in Edinburgh and contributed to debates over the Glasgow water supply from 1884-1886. They worked on various other water supply schemes for smaller cities and towns. Another major project was the development of plans for a major ship canal from the Forth to the Clyde via Loch Long and Loch Lomond which was never built.

Charles was constantly working on innovative design ideas and new technologies and was a regular writer in Nature and other scientific periodicals. Having observed new technologies on his travels including Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, Charles pushed for the development of better technology in Scottish lighthouses, particularly fog horns and flashing river buoys. He was particularly interested in sound engineering and, in 1893, published a paper for the Royal Society of Edinburgh describing how he had transmitted sound across space without wires. Later innovations included remote controls to activate equipment and the ‘talking beacon’- invented in collaboration with his son D. Alan - which allowed ships in thick fog to plot their location from radio signals.

Charles retired in 1940, having set up a new partnership with his son in 1936, A. & C. Stevenson, which Alan carried on without him.

Back to list(David) Alan Stevenson, 1891-1971

© Trustees of D. Alan Stevenson

David Alan Stevenson was the only son of Charles Stevenson and followed the now traditional educational path of Stevenson engineers. He studied engineering at the University of Edinburgh, graduating in 1912 with a BSc before joining the family firm as an apprentice. His apprenticeship lasted until 1917 and he was made a partner in the firm in 1919, aged 28. Following the family pattern, Alan was made an Associate Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1916 and a full member in 1925. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1919.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Alan, though still an apprentice in the family firm, was keen to contribute to the war effort. Because of his expertise in lighthouse engineering, he was specially commissioned as a Captain in the Royal Marines and travelled to construct lights in the Dardanelles as part of the Gallipoli campaign in 1915. He built five lights there before returning to Scotland. While the lighthouses were extinguished during the war, the firm continued to work on the other projects that they developed alongside the lighthouse business. This included advising on legal disputes and parliamentary enquiries, small scale harbour improvements and river management engineering.

After the war, the firm continued to work on these projects, as well as resuming its work on Scottish lighthouses. In 1925, Alan was made Lighthouse Engineer to the Government of India and was despatched to India to inspect and report on the state of lighthouses, harbours and beacons there and make recommendations for their future management.

He gradually took on more of the work of the family business as his father and uncle grew older and less capable of the travel, survey and maintenance required for many of their engineering works. Both men continued working from the office offering suggestions and directing operations into their eighties. In 1936 when Charles was 81 and David 82, the tension caused by this arrangement led to a split in the firm. Alan and Charles founded A. and C. Stevenson while David continued on for another two years alone, finally retiring in 1938, aged 84. He was replaced as Engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board by an assistant with the firm, so ending the family’s 151-year history in the post.

A. and C. Stevenson worked mainly as engineers to the Clyde Lighthouse Trust and in river improvement works more generally. Charles retired in 1940, leaving Alan in sole control of the business until he retired in 1952. Alan had three children, two daughters and a son, but none of them went on to become engineers.

In retirement, Alan became interested in the history of lighthouses and published The World’s Lighthouses Before 1820. He also served as custodian for the family history, collating and organising the firm’s collection of maps and plans and donating them to the Library in the 1950s. Most of the information describing the maps plans that has been made available in this resource comes from the typescript inventory created by Alan Stevenson and donated to the Library alongside the firm’s archive.