Beaufort's Surveyors in Scotland

by Brian Tiplady

A description of the main Admiralty surveyors, active in Scottish waters, during the first half of the 19th century: George Thomas, Michael Slater, Henry Otter, Charles Robinson, and Frederick Thomas.

Introduction

Francis Beaufort is probably best-remembered today for his wind speed scale introduced in 1805, and still in use: "Gale force 8" is familiar from the weather forecasts. But far more significant was his period as Hydrographer of the Navy, from 1829-1855. The Hydrographic Office was founded in 1795 to manage and distribute nautical charts for the Royal Navy. Thomas Hurd, one of Beaufort's predecessors as Hydrographer had, from the mid-1810s, started to develop a dedicated surveying service and made charts available to the to the public as well as to naval ships. Beaufort built on these policies, embarking on a surveying programme of world-wide scope, with Royal Navy surveyors working in South America, the Caribbean, Canada, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, and China. This period has been described by Steve Ritchie, Hydrographer from 1966–1971, as the "High Noon" of the Surveying Service [Ref 1]. Home waters were equally important. When Beaufort took office in 1829 there were 44 charts of Britain and Ireland, mostly of southern England. When he retired in 1855 there were 255 [Ref 2].

George Thomas

In Scotland, a number of notable surveyors worked on our often intricate coastline. In many places the Admiralty chart represented the first accurate mapping of coastal areas [Ref 3]. The first of these men, George Thomas, was already at work on his survey of Shetland when Beaufort took office. Thomas, an orphan at the age of eight, was admitted to Christ's Hospital, a charity school in London, the first "Bluecoat" school, so called because of the colour of the uniform. Here he received an education in mathematics and navigation before being sent as an apprentice on a whaling boat in 1796. The events of the next 10 years are unclear, but in November 1806 Thomas was among a number of sailors from the American Brig Harry and Jane pressed into the Royal Navy after their ship was intercepted during the siege of Montevideo [Ref 4]. This must have been one of the most successful conscriptions ever, because his navigating skills were recognised and he was quickly promoted to midshipman and then to Master's Mate. He became master in 1808, and in 1810 he was appointed by Hurd as Admiralty Surveyor. After working in southern England, Ireland and the Firth of Forth, he started his survey of Shetland in 1825.

Thomas was a very thorough surveyor, sometimes too thorough for the patience of Beaufort, who lamented the slow progress due to Thomas's "hypercritical precision". This was a bit much coming from Beaufort, who had included lots of detail of ancient sites in his charts of southern Turkey. But relations between the two were never seriously strained, and Thomas completed the survey at his own pace, moving on to the Orkneys in 1835. Here he was assisted by his son Frederick, of whom more later. Thomas's surveys continued to be the basis of published charts well into the 20th-Century [Ref 5]. Thomas was never promoted to officer rank, in spite of being in command of surveying ships, and being frequently commended for his work. He remained a Master, retired in 1846, and died a couple of years later.

Michael Slater

While Thomas was busy in the north, two other surveyors were working their way up from north-east England. In charge of this survey was Michael Slater.

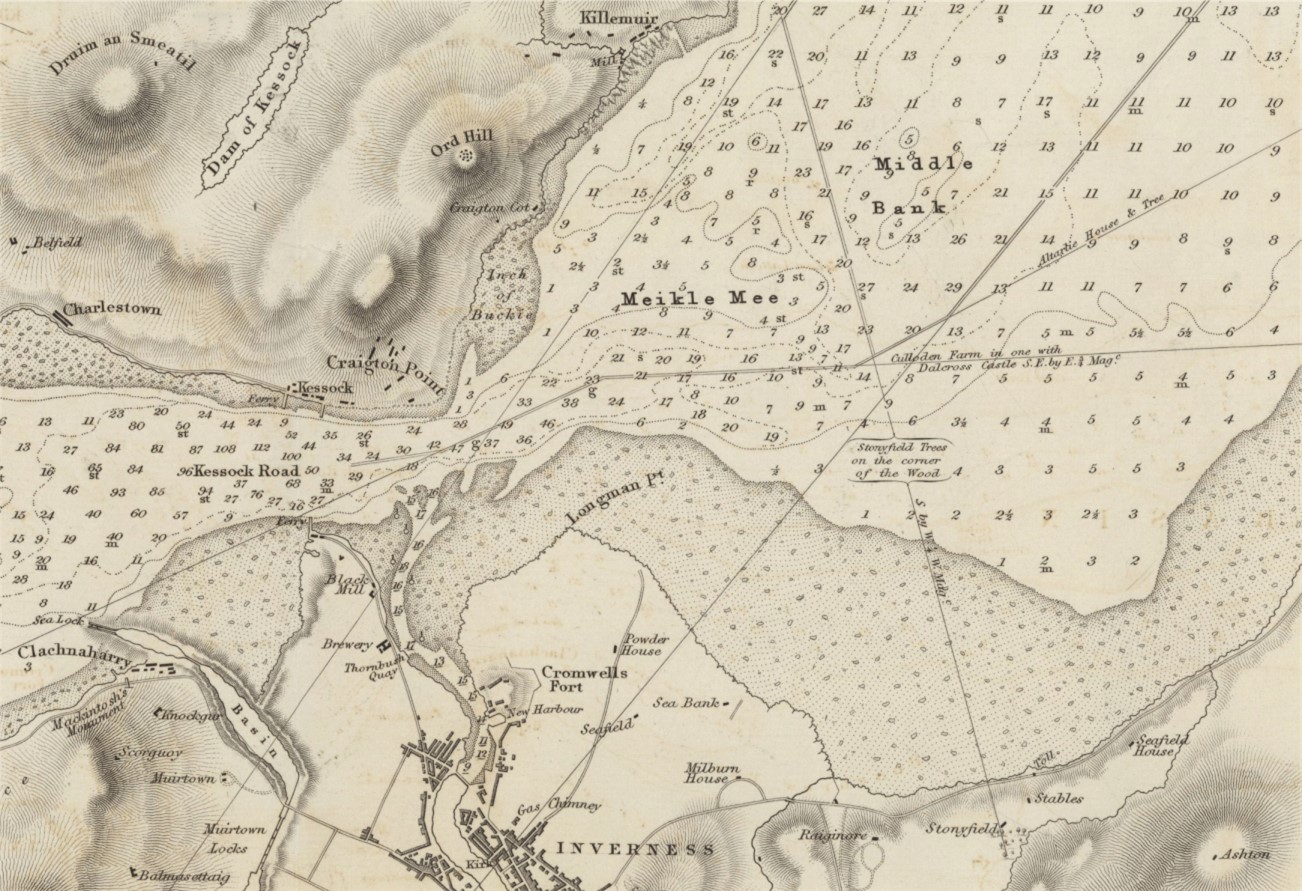

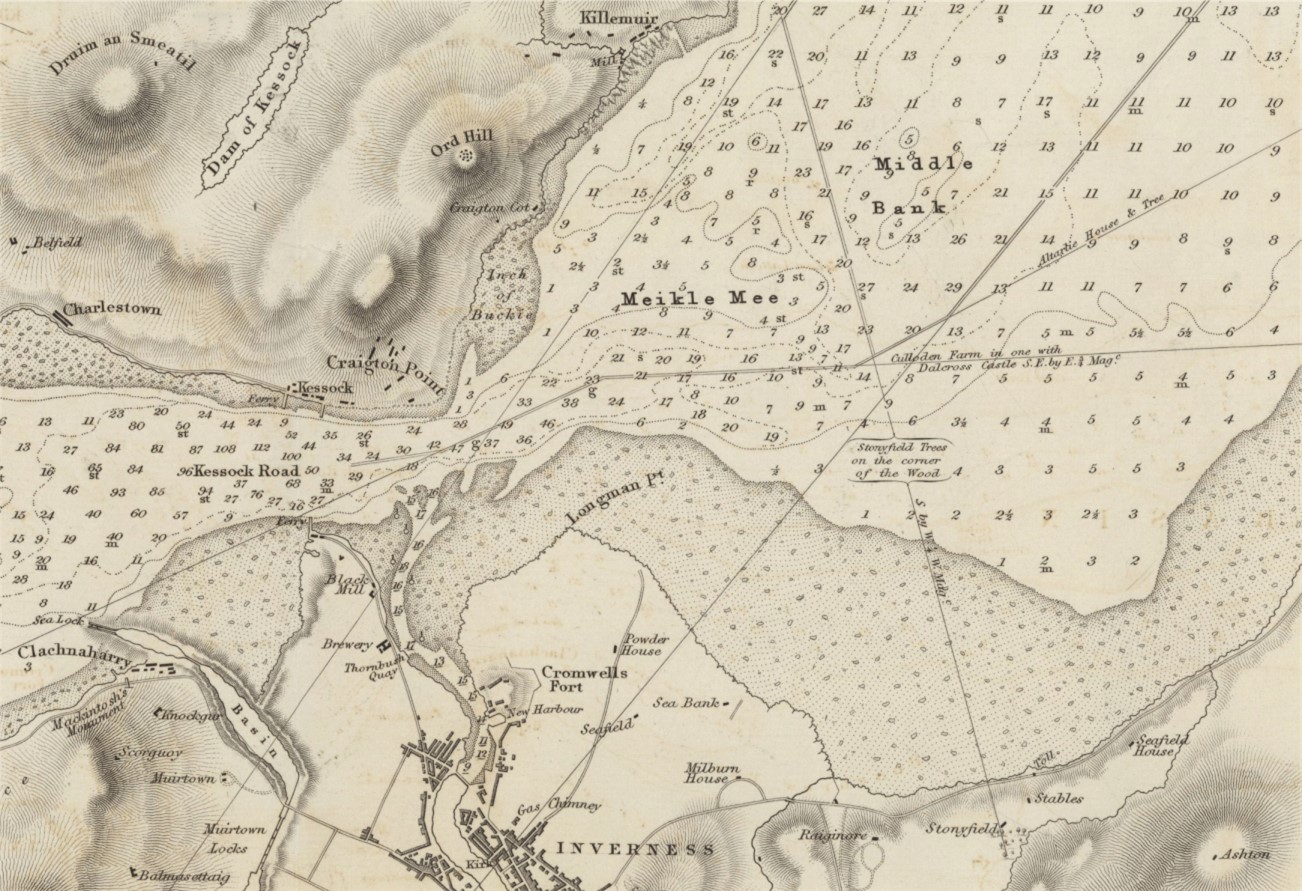

His father and brother were both artists (Fig. 1). In 1829 he started surveying the coasts of Durham, Northumberland and eastern Scotland. Survey data was important to planners as well as to mariners - in 1839 Slater was testifying before a Parliamentary committee considering improvements to the Caledonian Canal. He gave details of the hazards in the approach to the canal through the Moray Firth (Fig. 2), and made recommendations for the location of buoys and lights [Ref 6]. In 1842 he reached Dunnet Head, and connected with Thomas's survey of the Orkneys, completing the first adequate survey of the east coast of Scotland. Sadly he died that year, falling from a cliff near Holborn Head, NW of Thurso, believed locally to be a leap rather than an accident, as discussed by David Walker [Ref 7].

Henry Otter

Slater's replacement was Henry Otter, who had worked with Slater since 1832. His promotion to head of the survey was resented by two other Lieutenants on the survey who considered themselves senior to Otter, but Beaufort was not inclined to observe such considerations, preferring to select the man he thought best for the job [Ref 7]. Otter worked along the north coast to Cape Wrath. The name is from the Norse hvarf, the Vikings' "turning point" between the north and west coasts of Scotland. For anyone who has experienced the turbulent seas around this headland, the English word wrath seems equally appropriate, and the men who made the many hundreds of depth soundings with lead and line, mostly in open boats, must have felt the same! (Fig. 3).

Like the Vikings, Otter turned south into the most intricate part of the Scottish coast, the sea lochs and islands of the west coast and the Hebrides. He continued this work for nearly thirty years, with two breaks. The first was to serve in the war with Russia, where he was involved with surveying in preparations for military landings in the Baltic in 1854. The second, in 1858, was to take him across the Atlantic to support the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable. Back in Scotland, by 1867 he had reached Kintyre, the furthest south his surveys would reach.

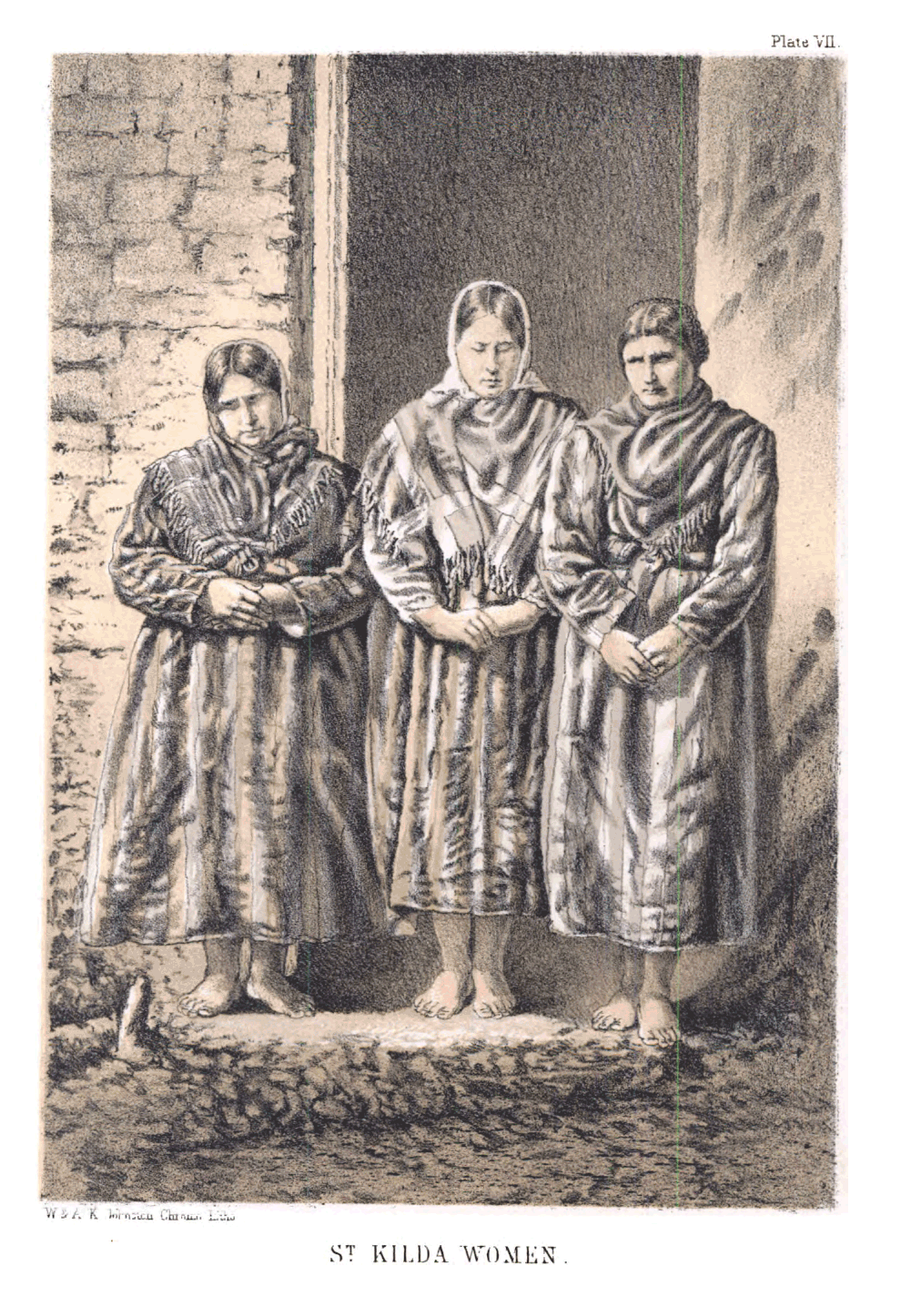

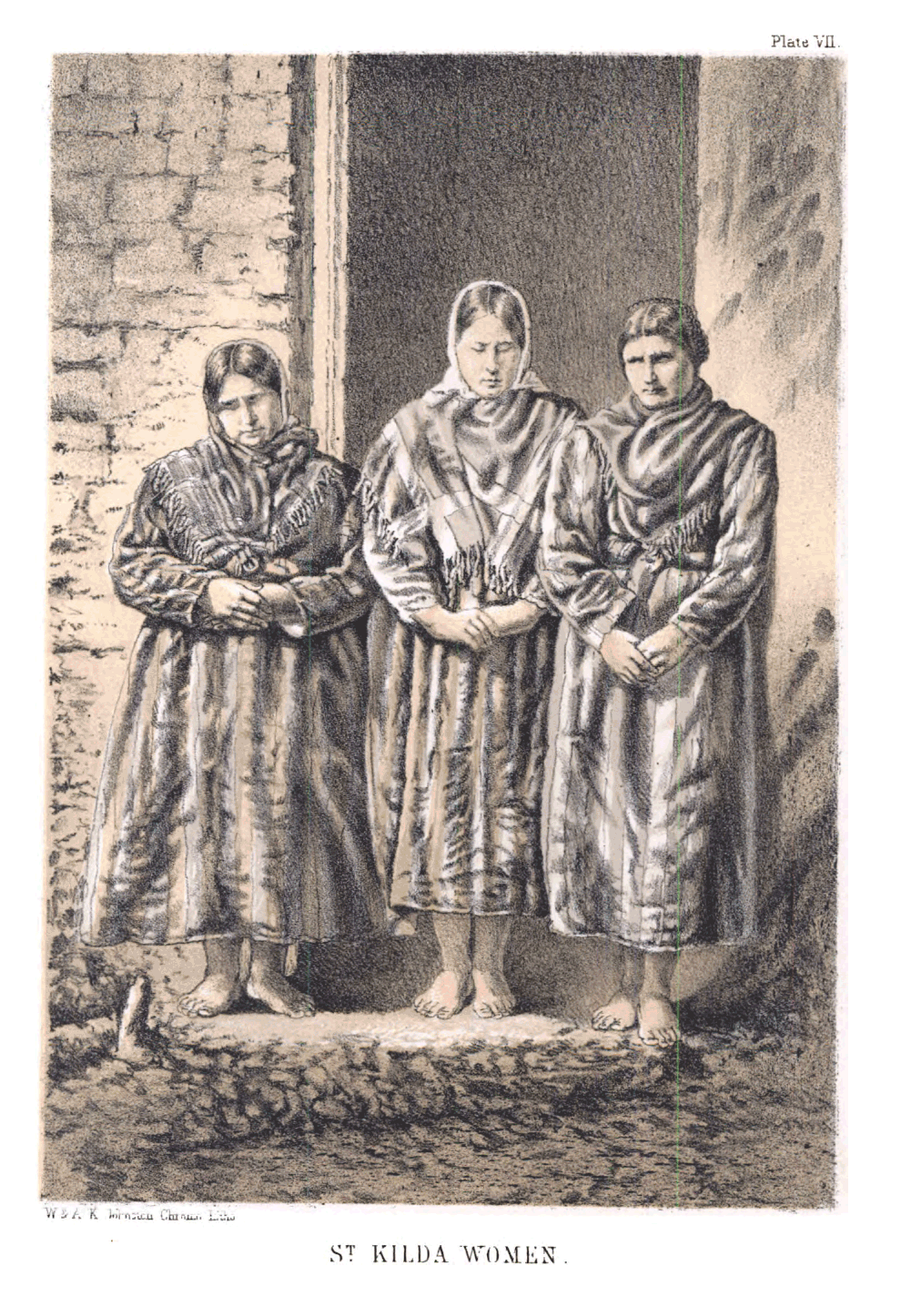

Henry Otter and his wife Jemima made their home in Oban, buying Manor House on the south side of the bay, in 1845 (Fig. 4). They were frequent visitors to St Kilda. Infant mortality on St Kilda was high, and the Otters believed that this was due to an oil-rich diet, particularly fulmar oil. When a St Kilda woman, Ann Gillies, was expecting a child in 1860, Henry and Jemima encouraged her in a diet of cocoa, meat and biscuit. Ann and her husband Norman had only two surviving children after 11 years together. This child survived and throve. The grateful couple called the child Mary Jemima Otter Gillies. Unfortunately diet turned out not to be the solution for infant mortality in general [Ref 10]. Otter retired in 1870, and died in 1876.

Charles Robinson

As Otter was working south from Cape Wrath, another of Beaufort's surveyors was moving north from the Solway Firth. Charles Gepp Robinson was about the same age as Otter. He worked with William Fitzwilliam Owen surveying in Africa in the 1820s. He was one of the few officers to return alive from this posting, which took a terrible toll through malaria and other tropical diseases. He then worked in Wales and the NW of England before moving into Scotland, surveying the Solway Firth and Clyde estuary in great detail, reaching Kintyre in the early 1850s, connecting with Otter's work.

In the churchyard of St. Michael's in Dumfries there was a memorial recording the deaths of two young sons of Lieutenant Charles Gepp Robinson, probably between 1836 and 1838, with the inscription: "Rest, my beloved boys. You were called away ere this world's sin could tarnish your bright hue" [Ref 11]. The boys' names were not recorded. I visited the churchyard last year, armed with M’Dowell’s 1876 account, and could not find the memorial stone. But some of the inscriptions are now eroded and indecipherable. There is another memorial raised by Robinson, on the island of Great Cumbrae, in the Clyde estuary. This records the deaths by drowning in 1844 of two young midshipman, who were caught by a squall when on a pleasure sail nearby (Fig. 5). It is natural to think that Robinson may have had paternal feelings towards these two promising young officers, particularly after the loss of his two sons, but this is just speculation.

Both Otter and Robinson had the benefit of using paddle steamers for surveying in the mid-1840s, Otter in HMS Avon, Robinson in HMS Shearwater. Beaufort had obtained six small paddle steamers for surveying in home waters in 1841. These manoeuvrable ships had many advantages for surveying work. But in 1847 the steamers were diverted to famine relief work in the west of Scotland and Ireland. And they mostly did not return to surveying work – in 1851 budget cuts meant a return to the false economy of hired boats. The one exception was HMS Porcupine, which was Otter’s ship from 1854. Robinson retired from the surveying service in 1853 [Ref 1]. In 1860 he was recorded as living in Oban. I can find no record of Robinson and Otter meeting, but they must surely have known one another.

Fredrick Thomas

The last of Beaufort’s surveyors in Scotland was Frederick Thomas, George Thomas's son. He joined his father's ship, HMS Investigator, in 1827, continuing the survey of Orkney after his father' death. He subsequently surveyed in the Firth of Forth, and also in the western Isles. Unlike his father he was promoted to officer class, becoming Lieutenant in 1841 and Commander in 1860.

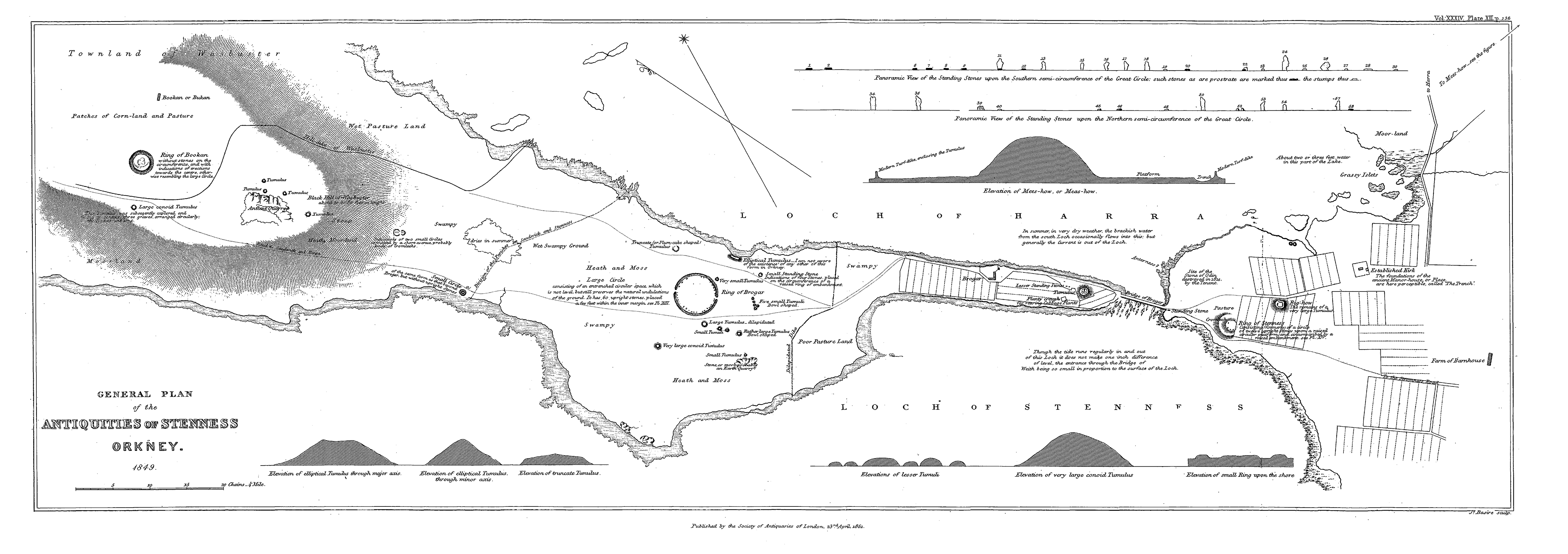

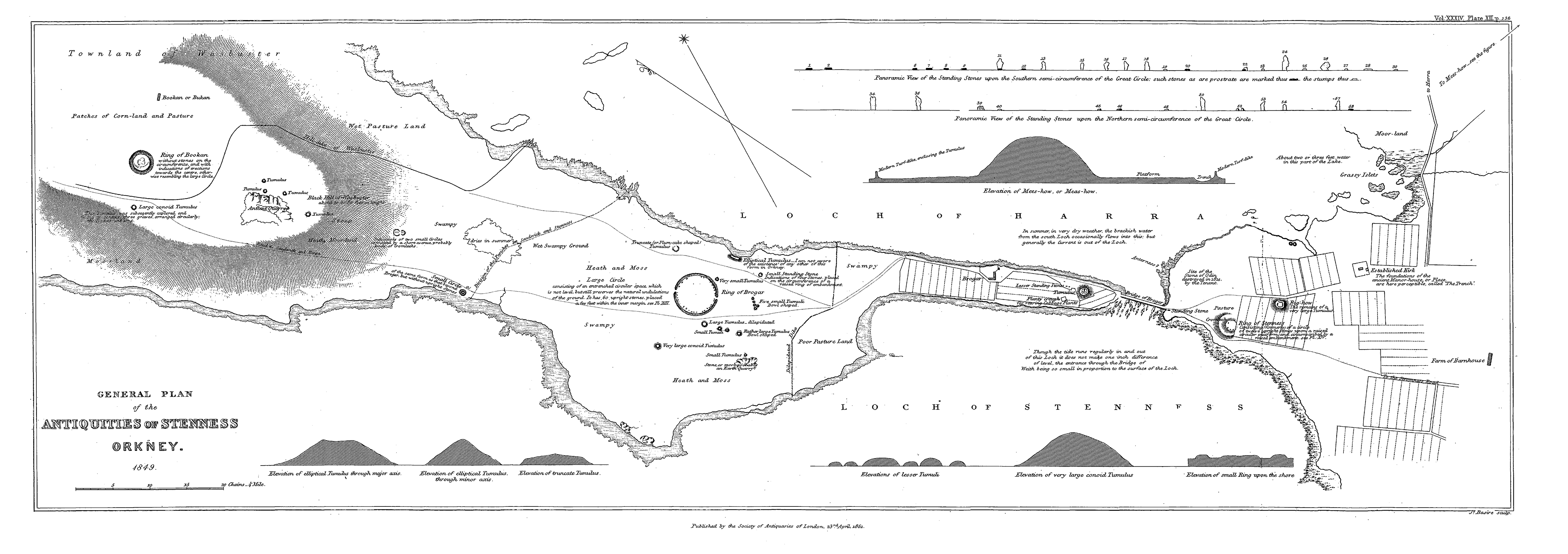

Like Beaufort, Frederick Thomas was interested in the archaeology and people of the places where he worked. He surveyed and recorded the barrows, standing stones and other structures around Stenness, in Orkney, providing the first detailed survey of this area (Fig. 6) [Ref 12] [Ref 13]. He noted the continuing use of beehive houses in the outer Hebrides, while elsewhere in Scotland and Ireland such buildings had been mostly abandoned. In 1857 he and his wife Frances set up home for a while in Harris. While there Frances helped to develop a market for Harris Tweed, to alleviate the poverty of the island. In 1860, Frederick Thomas sailed with Henry Otter to St Kilda, where he took the earliest photographs ever taken of the island (Fig. 7) [Ref 10] [Ref 14].

Beaufort, the surveyors he supported throughout his quarter century as Hydrographer, and the crews who took the many soundings and bearings, transformed not just the mapping of Scotland’s waters for navigators, but also mapping of much of Scotland’s coastal regions. No survey is ever final. Sandbanks and the channels between them shift or are dredged, cliffs erode, harbours are built, and lights buoys and landmarks change. But in my collection I have chart 1118b of the southern Shetlands. The edition is dated 1919, it was printed with corrections in 1950, and it still credits Thomas’s survey of 1833. The work of these men has withstood the test of time.

References

- Ritchie, G. S. 1967, The Admiralty Chart: British Naval Hydrography in the Nineteenth Century Hollis & Carter, pp. 189-199.

- Wallis, H. & McConnell, A. 1995, Historian's Guide to Early British Maps: A Guide to the Location of Pre-1900 Maps of the British Isles Preserved in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Cambridge University Press.

- Fleet, C., Wilkes, M., & Withers, C. W. J. 2011, Scotland: Mapping the Nation Edinburgh: Birlinn, p. 27.

- Walker, D. & Webb, A. (2018) The Making of Mr George Thomas RN, Admiralty Surveyor for Home Waters from 1810, The Mariner's Mirror, 104: 211-224. View online..

- Robinson, A. H. W. 1962, Marine Cartography in Britain: A History of the Sea Chart to 1855. Leicester University Press, pp.133-4.

- Report from the Select Committee of the Caledonian and Crinan Canals 1839. Parliamentary Papers: 1780-1849. House of Commons. View online.

- Walker, D. L. (2022) Slater's Loup and Monument - and his successor, Henry Otter, Cairt Issue 40: 2-4.View online.

- Admiralty Chart No 1451, Firth of Inverness and Beauly Basin, published 1846. View chart online.

- Admiralty Chart No 1954, Scotland north coast sheet 6 Thurso to Cape Wrath, published 1846. View online.

- Hutchinson, R. 2016, St Kilda: A People's History. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- M'Dowall, W. 1876, Memorials of St. Michael's: The Old Parish Churchyard of Dumfries. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, p 100. View online.

- Thomas, F. W. L. (1851) Account of some of the Celtic Antiquities of Orkney, including the Stones of Stenness, Tumuli, Picts-houses, & c., with Plans, by F. W. L. Thomas, R.N., Corr. Mem. S.A. Scot., Lieutenant Commanding H.M. Surveying Vessel Woodlark, Archaeologia, 34: 88-136. View online.

- Fleet, C., Wilkes, M., & Withers, C. W. J. 2016, Scotland: Mapping the Islands. Edinburgh: Birlinn, p. 38.

- Seton, G. 1878, St Kilda Past and Present William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh. View online.

Further reading

Biographies of all the surveyors mentioned here can be found on Wikipedia: